An Unsung Heroine: The Life & Radical Activism of Jewell Mazique

EDITOR'S NOTE

Richard D. Benson II is a historian specializing in education, the Black Freedom Movement and transnational social movements. He completed a PhD in Educational Policy Studies specializing in the history of education at the University of Illinois. He is currently an Associate Professor in the Education Department at Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia. He has received a number of grants and awards including the UNCF/Mellon International Faculty Residency, The W. E. B. Du Bois Visiting Scholars Fellowship at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and the New York Public Library Fellowship. He is the award-winning author of Fighting for our Place in the Sun: Malcolm X and the Radicalization of the Black Student Movement 1960-1973 (Peter Lang Publishing, 2015). Dr. Benson is currently working on a book manuscript entitled, Funding the Revolution: Black Power, White Church Money, and the Financial Architects of Black Radicalism1966-1976 (State University of New York Press, 2019).

The past decade has given rise to the overdue acknowledgement of Black women of the Black Freedom Movement. Scholars such as Ashley Farmer, Erik McDuffie, Brittney Cooper, Robyn C. Spencer have produced critical scholarship that has shifted the male dominated historical narratives, which have underserved the roles of Black women in the freedom struggle. Black women of the Movement have undergirded the literal “movement” and organizational activities of key formations that have defined personalities, organizations, policies and thought. However, historical amnesia of the Black Freedom Movement undergirds how the so-called master narratives represent Black women.

The overall Movement has not recognized a plethora of Black women whose personal sacrifices helped advance the struggle. Among this group of women are Ruby Doris Smith-Robinson (1942-1967) of SNCC whose commitments aided in the development of the vanguard student organization; Gloria Richardson Dandridge whose leadership of the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee aided greatly in training many SNCC students for nonviolent direct action and protests in the early 1960s; Florence Tate (1931-2014), who joined the movement as a journalist from Dayton, Ohio, and was active in the Congress for Racial Equality, Friends of SNCC, Malcolm X Liberation University, and an integral organizer of African Liberation Day 1972. However, a groundbreaking forerunner to the aforementioned Black women who remains mostly nameless in recent scholarship is the legendary radical Black woman activist Ms. Jewell Mazique (nee Crawford, 1913-2007).

Ms. Mazique was an organizer, civil rights activist, writer, scholar, education advocate, and mentor and consultant. From the 1940s through the 1980s, Ms. Mazique, while based mainly in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area, shared her expertise with a number of organizations of the Black Freedom Movement to combat racial injustice. As a leading figure for racial equality, Ms. Mazique contributed significantly to the development and progression of many prominent ‘leaders’ for Black liberation. As one of the Black women who tutored Black men who have taken sole credit for their own brilliance, Ms. Mazique was member to a number of “shadow cabinets” as she advised Black radical activists, students and African heads of state including Malcolm X, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Julius K. Nyerere of Tanzania. However, prior to engaging revolutionaries and heads of state and prior to being dubbed “Mother Africa,” Ms. Mazique had received an excellent education that prepared her for social justice activism,which was foundational to the overall Black Freedom Movement.

Born Jewell Crawford on October 2, 1913, in Georgia, Ms. Jewell Mazique was a Black woman of mixed native American Creek, Cherokee and African heritage. She graduated from Spelman College in the 1935 and later moved to Washington D.C. to attend Howard University. While at Howard, she met her future husband and medical student, Edward C. Mazique. She eventually gained her masters degree from the African Studies Department at Howard, where she completed her thesis on the development of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Ms. Mazique earned the honor of being the first recipient of a M.A. in African Studies at the Historically Black College/University. After graduating from the Howard University, Ms. Mazique worked two jobs to support her family and put her husband Edward through school. During this era, the early 1940s,Ms. Mazique worked for the federal government as file clerk in the Library of Congress.1

The Maziques were able to establish their family as a part of D.C.’s Black elite during the war period. However, Mazique, a developing radical community organizer, feminist, union organizer and member of Delta Sigma Theta, held no interest in ascending the Black bourgeois social ladder. Mazique who not only invited social activism but also preferred social justice over socialitism remarked that “The frills of social life hold no charms for me, I am more concerned for instance with what the political leaders of Paris decided to do about their colonial possessions than what the Paris designers decide about what women will wear.”2 espousing this philosophy, Mazique made her mark politically as a co-founder of the Capital Transit Campaign, which fought to eradicate job discrimination in D.C.’s public transportation system.

Battling against Jim Crowism in the nation’s capital, Mazique organized protests, picket lines and attended mass meetings and congressional hearings.

Despite her desire to avoid the limelight, in 1942 Mazique became the subject of photographer John Collier Jr.’s photographic series on Black employees of the Office of War Information. Used as a propaganda ploy by the Office of Coordinator Information to provide a perspective of Black workers in the Federal government, the photographs were supposed to display the American mobilization efforts during wartime while capturing the day in the life of Mazique from her place of work and her home with family. However, what wasn’t captured by John Collier but was common knowledge for those ‘in the know’ of Black activist Washington D.C. was the fact that Ms. Jewell Mazique was a tireless activist for Black liberation.3 In 1943, Mazique eventually left her job with the Library of Congress and fully devoted her time to the efforts working as a columnist for the Washington D.C. and Baltimore AFRO-American Newspaper; and sharing her expertise as a Specialist for the Elks Civil Libertie League and an elected member of the Woman’s Auxiliary to the National Medical Association, where she served as the editor of the Mouthpiece Newsletter.4

By 1945, Ms. Mazique served on the National Council for the Southern Youth Negro Congress (SYNC), an organization that was identified to be a Communist front organization. Working as corresponding secretary for SYNC, Ms. Mazique worked with notables such as Esther Cooper Jackson to protest in Washington, D.C. and demand that the United States government move to fully integrate the “armed forces, including ROTC programs, the Air Corps, its training centers, officer training schools, and the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps.”5 As a fearless Black woman activist, Mazique maintained a critical stance on social injustice and chided the federal government for their unwillingness to address anti-Black violence in the South against citizens who attempted to exercise their right to vote. In a 1960 hearing held by the Volunteer Civil Rights Commission, fifteen hundred people gathered to address the vices of collusion between the Federal Bureau of Investigation and racist organizations of five southern states and the District of Columbia that vigorously withheld the voting rights of Black folks in the respective jurisdictions. Representing the Washington Elks Civil Liberties League, Ms. Mazique delivered a scathing critique of the socio-political climate of the nation and spoke of both Black and poor white exploitation in the nation’s capital. Not mincing her words, Ms. Mazique blasted the so-called allies of the movement as “those phony northern liberals who masquerade as civil rights exponents.”6

As a woman well informed in international affairs, Ms. Mazique maintained a deep engagement with global happenings. Thus, an activist engaged in theory and practice, Ms. Mazique traveled extensively to increase her transnational political awareness. For example, when Jet magazine covered the ‘vacation with a purpose trip’ of the Washington chapter of the National Council of Negro Women, she was one of 32 Black women who traveled to fourteen countries in thirty-two days to conferences and meetings with women leaders in those respective countries. That same year, Ms. Mazique, the only Black woman of a thirty-person delegation, traveled to the Soviet Union block during the Cold War to engage with political leaders in several Soviet countries as part of a post-Sputnik mission.7

Arguably more fiery than her rhetoric, was the prodigious prose she contributed to a number of newspaper outlets in in the Washington, D.C. and Baltimore areas. Her writings ranged from critiquing the position of the United Nations on Africa to the treatment and education of Black children in the Washington D.C. public school system. Ms. Mazique’s articles even attracted the commendations of notables such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Horace Mann Bond.8 Ms. Maziques critical and polemic style was definitely captured in a 1960 article she penned for D.C.’s AFRO-American newspaper entitled, “Africa, Beware of Trade Union Imperialism.” The open letter, which was also reprinted in the Ghanaian Times, critiqued the United States’ labor history on race relations, the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions and Tom Mboya.

In her piece, Ms. Mazique praised the leadership of President Kwame Nkrumah and applauded his foresight for not allowing outside imperialist forces “to direct Africa’s destiny through ‘Uncle Toms’ who would set African against African.”9 However, one of Ms. Maziques’ most impactful works is an article (1965) entitled, “The Emergence of the African Personality,” wherein she describes Christianity as seen by many Africans as an “adjunct of colonialism.”

This period in her life was met with a personal and familial challenge as she and her separated husband Dr. Edward Mazique became embroiled in a divorce that attracted public attention in the early fall of 1964. Ms. Mazique acted as her own counsel in a divorce case that found her fighting for additional financial support for herself and her sons. Ms. Mazique argued that because she supported her husband through medical school by working two jobs, the court should consider awarding her financial support to include payment for the house. Nonetheless, the court discounted the expense of their home in their evaluations and Ms. Mazique lost the case. She later appealed the decision in 1965 for additional financial support, claiming that the courts were biased toward men. Although she eventually lost the appeal, she remained steadfast in her career as an activist during the era of the Black Freedom Movement.

During the 1960s as the Black Freedom Struggle evolved into the international moment of “Black Power,: the role of Ms. Mazique as a mentor grew to new heights of importance with the emergence of radicalized Black activists who challenged the government and anti-Black injustices. This became evident when Congressman Adam Clayton Powell identified Ms. Mazique for the planning committee for the first national Black Power Conference held in Newark, NJ, in 1967. As the Black Power movement morphed into the resurgence of the Pan-Africanist movement of the early 1970s, Black activists from around the globe prepared for a historic showing of Black Internationalism on the African continent by planning for the Sixth Pan-African Congress in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Former SNCC activists Courtland Cox and James Turner were now at the helm of planning the conference, and they extended an invitation to Ms. Mazique to attend the conference in Tanzania. A seasoned activist who was battle tested by years of activism, Ms. Mazique was experienced enough to know that Cox and Turner needed to be questioned and assessed as well prior to accepting their invitation. In an April 3, 1974, correspondence, Ms. Mazique, without mincing words, conveyed her apprehensions to Cox and Turner: I have sometimes tested out the sincerity of Negro/Black Politicians, who write you letters of support and when you turn up at their offices in Congress of the city administration they duck you…this is but one measure of how far removed we, the culturally deprived, economically disadvantaged victims of developmental disabilities are far from our would be successful Black brothers…I sincerely trust the African “natives” are closer to their culturally privileged elites over there than we are here in the United States: if not we, all of us, are in serious trouble.

Providing leadership through her consultation as a committee adviser and attendee to conferences was a contribution to the Movement. However, one of Ms. Mazique’s greatest strengths was her ability to mentor younger activists through instruction and tutelage. Scholars investigating the life of Ms. Jewell Mazique are challenged by the sparsity of primary sources on her life. One of these investigations has led to the discovery of a significant October 1,2004, interview provided by Akyaaba Addai-Sebo, the founder of Black History month in the United Kingdom. In the interview, Addai-Sebo spoke candidly about his life of activism that spanned the African continent, the United Kingdom and the United States, and he identified, his “master teachers,” including CLR James, Chancellor Williams, and John Henrik Clarke. Addai-Sebo then spoke candidly about Ms. Jewell Mazique:

I remember quite well Madam Jewel Mazique who also took me under her wing

for about three years. She disciplined me to get up at about 4am and go to her

house. There was a particular chair that she would ask me to sit on. She would say:

‘You sit here. That was where Malcolm X used to sit.’ So I have been very lucky.

Jewel Mazique was the first African-American woman to graduate with a Masters

Degree at Howard University, and she was a very marvellous woman, very strong

and a visionary. She was called Mother Africa. And Julius Nyerere, who became

president of Tanzania, Nkrumah and all of them knew her when they were in the

They used to go to her. So I was lucky, just lucky.

Though ‘luck’ may have played a role in the three-year opportunity of menteeship that Addai-Sebo received from Ms. Mazique, it is certain actions were not sporadic nor misplaced.

And as with Addai-Sebo, Ms. Mazique continued to act as a mentor and as an activist into the twenty-first century before her passing at the age of 94 in 2007. In sum, Ms. Mazique’s life speaks to planning, strategy, investigation, research, leadership and advocacy for social justice.

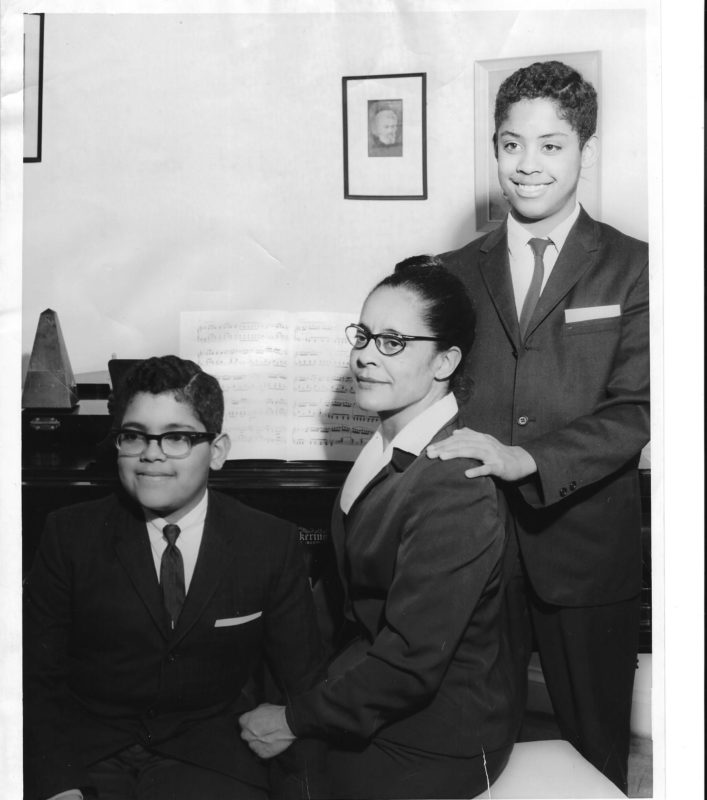

Ms. Mazique’s sons, Edward and Jeffrey,echoed supportive sentiments of their mother’s role as a proponent of activism. In a 1982 letter of correction and apology from the AFRO-American Newspaper, Edward and Jeffrey refer to their mother’s heroic actions by referring to how she benefited “young people who have come under her noble spirit” and how

their mother taught them the “communal African concern for one’s fellowman and the pursuit of knowledge, the basic fundamentals as essential to enlightenment and productive activity.”12 These qualities undergird activism for less fortunate people but more importantly, they are the momentous attributes that prepare leaders, guide movements, provide organizational planning, expose youth to political education and model longitudinal revolutionary activism. Ms. Jewell Mazique was without question such a figure and definitely an “unsung heroine.”

Share to your favorite social media page

Follow Us

Fans

Fans

Fans

Fans